Sex After Cancer

Helping female survivors regain their sexual satisfaction and confidence

After Naomi’s breast cancer treatment — the lumpectomy, the chemotherapy, the 33 radiation treatments — she lost her desire for sex. But she wanted to please her husband, so she had sex with him. And bled for three days.

“The bleeding was unbelievable, and the pain was so much I could hardly take it,” says Naomi, a Bronzeville resident who asked that her last name be withheld due to the sensitive nature of the topic.

“I didn’t know what to do. I thought that was supposed to be my life from then on. I felt less than a woman. I had extremely high anxiety and depression,” says Naomi, a 68-year-old clinical massage therapist. It went on like this for years.

Naomi’s doctors never asked about this part of her life, so she suffered in silence. Then she found her way to Stacy Tessler Lindau, MD, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at UChicago Medicine and director of the Program in Integrative Sexual Medicine for Women and Girls with Cancer (PRISM).

“[Lindau] started asking about my sex life. It just floored me that I wasn’t alone; that other cancer survivors were going through the same thing,” Naomi says. “She said she would help me. It changed my life.”

Preserving sexual function

Lindau knows many women like Naomi and says they often live with fear, shame and embarrassment because of their sexual problems.

In 2010, Lindau was the lead author of a study that found many women who survive breast and gynecologic cancers want medical help for their sexual issues but most do not get it.

Multiple datasets show that the incidence of sexual dysfunction ranges from 30 percent to 100 percent among female cancer survivors, according to a review in The Oncologist. The authors write that multiple barriers, such as time constraints, keep providers from engaging in sexual health discussions, but “taking a sexual history of our patients becomes as important as understanding their past medical and social history.”

At the PRISM clinic, specialists in gynecology, psychiatry, physical therapy, oncology and nursing work to change this pattern. “We’ve seen some growth in programs that seek to help women recover sexual function,” Lindau says, “but we’re far from providing care in this domain that prevents unnecessary pain and suffering for women and their partners.”

They clump sexual well-being into one of those losses that cancer took away.”

By contrast, she says, men have more resources on the topic. Twenty years ago, when Bob Dole did commercials for Viagra in the context of his prostate cancer, it changed the conversation about sex after cancer for men.

“We haven’t had a spokesperson like that for women,” she says. “It’s a health equity issue.”

Raising awareness

Chicago has become a hub for raising the level of awareness around sexual function for women living with cancer. Last year saw the opening of the Center for Sexual Medicine and Menopause at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Medical director Lauren Streicher, MD, says that about 50 percent of patients come because of issues related to cancer treatment.

With more women surviving cancer, it’s critical to discuss sexuality, says Streicher, author of Sex Rx: Hormones, Health, and Your Best Sex Ever.

According to the Mayo Clinic, the most common sexual side effects for women after cancer treatment are:

• Difficulty reaching climax

• Less energy for sexual activity

• Loss of desire for sex

• Pain during penetration

• Reduced size of the vagina

• Vaginal dryness

Also, sexuality after breast cancer can be affected by the loss of part or all of a breast (or breasts) after surgery.

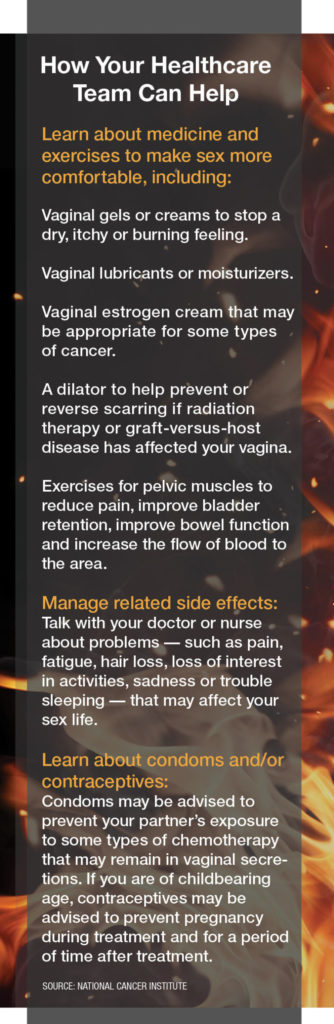

“Even after treatment, there is a cloud hanging over women’s heads,” Streicher says. “Many women are given an antidepressant, [which] can have an effect on libido.” In addition, chemotherapy and radiation can often cause early menopause and all the symptoms that go with it, such as thinning and shortening of the vagina.

“Too often women feel, ‘That’s the way it is, and I should be glad to be alive,’” Streicher says. But women shouldn’t settle for that. “We certainly are able to alleviate many of the consequences of menopause or cancer treatments and restore sexual function. If your doctor doesn’t help you, that doesn’t mean help isn’t available.”

Promoting sexual well-being

Catalina Lawsin, PhD, director of psychosocial oncology and integrative medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, says it’s understandable that sex is not at the top of the list after a woman’s — or a man’s — cancer diagnosis.

“They’re just thinking, ‘I just want to get cured.’ Sexual side effects are not talked about,” she says. “They clump sexual well-being into one of those losses that cancer took away.”

“When they’re feeling distressed, they tend to generalize [and think], ‘I’m never going to have sex again.’ We talk about how we can neutralize that thought and say, ‘I might not be able to have sex when I’m in pain, but I can look for times when I can plan sexual activity.’” From open communication to medication to sex toys, there are ways to reignite sex after cancer, Lawsin says.

Single people who are dating have another challenge: when to bring up their cancer diagnosis.

“They wonder [whether] they want to bring up the diagnosis. Will it turn this person off? How many dates into it? Each person has to decide,” Lawsin says.

At UChicago Medicine, Lindau and her team recently launched WomanLab, a platform for personal and informational essays and videos about sex — starting with sex and cancer and including sections on self-care and what to do before, during and after cancer treatment.

Naomi says that before she learned what to do, “I didn’t care if I lived or died.” But eventually, she found a solution. A gynecologist examined her; a psychiatrist helps with her anxiety and prescribed medication for her depression; and a pelvic floor therapist treated her vaginal tightness, taught her relaxation breathing and advised her about lubricants.

“It brought me life,” she says. “Sex stopped hurting. It was embarrassing for me to talk about it, but now I am so open and so free, and I [feel] no shame.”

Questions for women to ask before starting cancer treatment

1. Are there treatment options that would give me a good cancer outcome and also preserve my sexual function?

2. Do I need to stop having sex? If so, how will I know when it’s okay to start again?

3. Will chemotherapy affect my sexual function?

4. How will surgery affect my ability to have normal sexual arousal and pleasure?

5. Will blocking my ovaries from making estrogen affect my sexual function?

6. How will radiation to or near my sexual organs affect me?